Q&A with CareFirst Leadership: Your Questions Answered

Two representatives from CareFirst, Brian Wheeler, VP, Practice & Payment Transformation and Deb Rivkin, VP, Government Affairs for Maryland participated in a Q&A session on issues critical to our membership at our September 10, 2019 Executive Board Meeting. Their opening presentation can be viewed above.

The following are their responses during the Q&A, edited for clarity. The session was facilitated by MCMS President Lawrence Green, M.D. MCMS thanks Brian Wheeler and Deb Rivkin for appearing and for their candor.

Access to Care

Question: In MCMS’s 2019 Practice Survey, 82% of physician respondents indicate that the greatest threat to patient care in our community is the increased administrative burden on clinicians which has reduced face time with patients. The second most significant threat is the lack of affordable health insurance options for patients (deductibles are too high, high copays, etc). Premiums continue to increase as do high deductible options in our marketplace. Patients are putting off care or not seeking care they need as a result even though the individual mandate is still in place. What is CareFirst’s vision for more affordable, accessible coverage for the future?

Brian Wheeler: There’s the rising cost of healthcare has caused the market to do all these goofy things like high deductible health plans. I think if we had our druthers, we would not have any high deductible health plans. We like patients to have access to care for a reasonable cost. We don’t want it to be $250 to see a specialist or to get a procedure done because we understand that causes people to put off care.

In the late 90s, early 2000s, when the trend was 8, 9, 10% per year, employers would get their annual insurance renewal and the insurance broker would say, your coverage is going up 12% next year. And they would say, I can’t, nothing else in my budget’s going up 12% next year. I can’t afford 12%. They would say, well, I can give you only a 6% rate of increase but, you’re gonna have to take a high deductible for your employees. And there you go. The high deductible health plan was born, then somebody on Capitol Hill came up with a brilliant idea that consumers were really good consumers of health care and that if they could just have high deductible health plans with their own special savings account, that they would be really smart shoppers and make good healthcare decisions.

Anybody think that worked? [laughter] This is the way of the market. It’s a reaction to the skyrocketing costs. The market created this mechanism of a high deductible health plan and consumer directed health care and we’re kind of stuck with it.

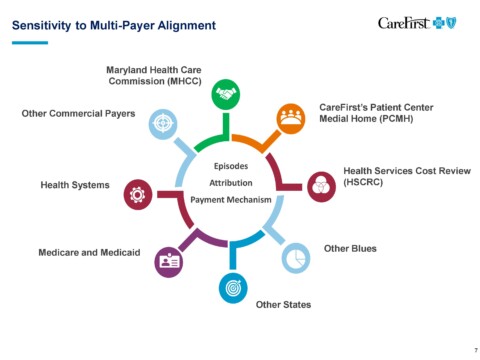

Deb Rivkin: If I can jump in and give the political version of the answer. Part of the problem is, utilization hasn’t changed. You can see it’s still going up. And illness burden for our members is going up. It’s not going down. And even when we do things like for our PCMH program where we’ve seen decreases in admissions and readmissions and we’ve avoided care costs that would have been there if we did not work with the provider community in our PCMH program. The trend is still high, so what you heard Brian say before is that 30% of our healthcare dollar is going to pharmacy. That out spends physicians, specialty, hospital stays.

Brian Wheeler: It’s bigger than inpatient now.

Deb Rivkin: It’s bigger than everything. That’s not changing and the trend is just going to go higher and higher. So what ends up happening is the healthcare dollar is the healthcare dollar, right? When we get our rates approved, it’s based on utilization, costs incurred, and trend projections. We get them approved by the insurance administration, so it is a highly regulated process where they analyze the data that we give them and they determine whether or not what we’ve said is correct. When we design a plan, there’s only two things. You’ve got your premium and out of pocket costs because the plans will cost a certain amount of money, right? Say, $100. So we have to decide, how are we going to split up that $100? In your premium, or in your out-of-pocket costs? Part of the philosophy is, if you lower the premium, people can get in the door, they can buy the insurance, they can get the coverage, but as you’ve reduced the premium out-of-pocket, costs go up. That’s part of the struggle we have in trying to design plans and especially now in the individual market under the ACA, there are actuarial value levels. We have to design plans within a certain value and we can’t just say, oh, based on that premium, that’s too high of an out-of-pocket cost. We want to reduce them. Our products would be rejected by the calculator. So there are certainly constraints we have, but we’re very cognizant of this. That’s why we’ve been really focusing on our PCMH program and what we’re doing with the value-based programs.

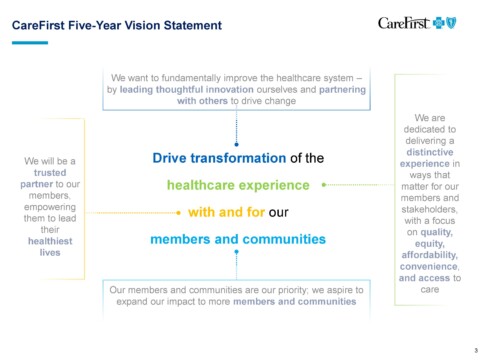

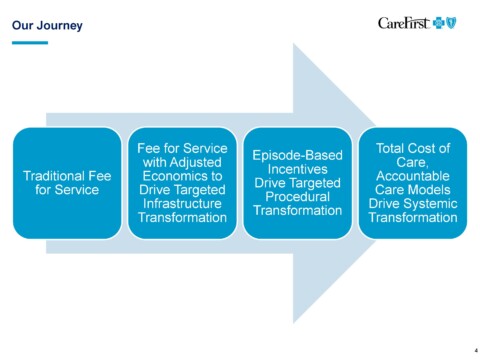

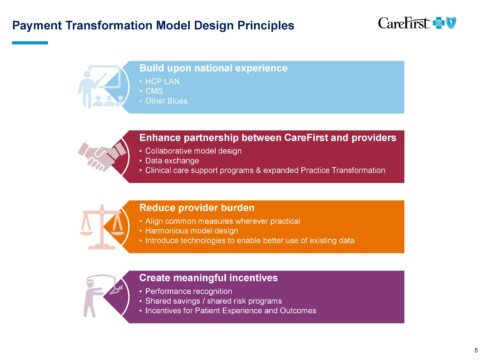

Brian Wheeler: Our plan is to move to value based payments within five years. Our goals is to have the rate of growth in healthcare costs match that of wage inflation. That’s where we want to be in five years. Then we’re going to be working with all of you and all your colleagues across the state and the District and Virginia to figure out how to do that.

Quality of Care & Coverage Decisions

Question: Physicians trained for many years in their respective specialties. We are in the best position to be able to define quality. However, our decisions are constantly being questioned by payors seemingly driven by mostly by economic factors, not what is best for the patient. What is CareFirst’s process to define quality of care and who makes quality of care decisions?

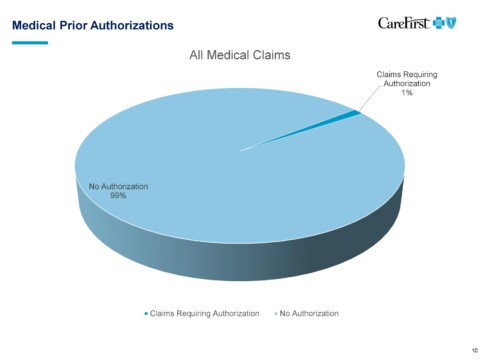

Brian Wheeler: The first thing I would note is that the data suggests that it’s on a very small number [of claims]. And I recognize that in certain specialties it may be pocketed and it may feel like there’s more of a process to go through to get things paid. I would again say, make sure that when you’re hearing about the challenges of insurance companies, you make sure you know which insurance company you’re talking about or your office staff is talking about.

Deb Rivkin: We really look at the national guidelines and national standards. When you look at prior authorizations, for example, the law says that in Maryland you have to develop standards that are nationally vetted, and are real, true standards. You can’t just make something up. We have to submit those to the insurance administration. We really do try to ensure that we’re looking at national guidelines.

Lawrence Green, M.D.: Not to interrupt, but I’d like to ask quickly: By the time these national guidelines come out- we’re frustrated that you’re looking at guidelines that aren’t really relevant. I don’t know if it’s anyone else but me, but I think that’s part of the issue we’re seeing.

Deb Rivkin: When we look at the different requirements, we’re looking at NIH guidelines and CPT, so you can imagine how difficult it is for a company who’s trying to ensure that we are doing quality care. We have to have a benchmark. They might not be perfect. There has to be a benchmark now.

Question: Insufficient coverage leads to unnecessary hospital readmissions and/or duplication of tests, etc. How are these decisions made and by whom? Are practicing physicians a part of the decision-making coverage decision?

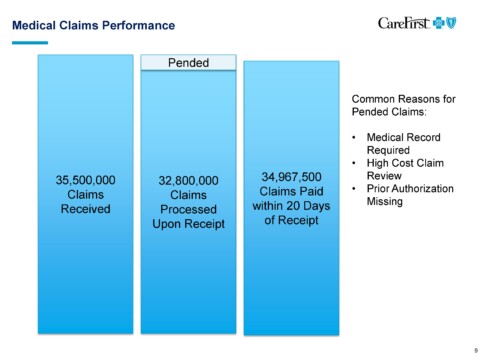

Brian Wheeler: We have a chief medical officer who is not practicing, but our chief medical officer guides our policy decision making process. We bring physicians in from the community to participate in various committees to help us set medical policy, review medical policy. We have a technology evaluation committee as well, comprised of internal and external physicians who review emerging medical technology and make coverage decisions based on that. And then when there is something particularly esoteric that comes through and may end up in an appeal, we have what’s called independent review organizations that are practicing physicians in various specialties who would review a particular case and make a coverage determination. Now we only get about 17,000 appeals per year out of the 35 million claims. So it’s pretty rare that it happens. But those kinds of things are available and they’re part of our processes and they do involve physicians practicing in the community in various specialties.

Question: According to MCMS’s own 2019 Practice Survey, most physician respondents think quality of care is the same or worse despite advancements in technology. What are your thoughts about their observations?

Deb Rivkin: It’s interesting to me because everyone’s moving towards electronic medical records, electronic communication, tele-health, which is electronic. We’re all moving that direction and it’s supposed to make our lives easier, but it’s not. We’ve got to figure out how to do a better job. Because I can tell you-to push back slightly- (Dan has heard this a hundred times from me) several years ago, actually it was around seven years ago, MedChi was the proponent of a bill in Annapolis to require electronic pre-authorization. It was the medical society that asked for it. We were, over several years as an industry, to hit certain benchmarks to ensure that every provider physician had the ability to do electronic pre-auth for medical decisions and also pharmaceuticals. The pharmaceuticals, for example, you got real time results if you put in the data. The goal was to reduce your administrative burden. Have more consistency, get faster results. It was all supposed to be a good thing. We all jumped through every hoop to get it done. 40% of providers are using CareFirst’s system today. In seven years, you still can’t even break 50%. So it’s something we can continue to talk about, but that’s frustrating on our end because then that means we’re getting paper, we’re getting faxes, and we have to go through that. Every one increases workload and makes for a much slower process. So we’re going to have to work on that together.

There was a bill last year in Annapolis. MedChi and CareFirst took the lead on this, the bill you all put it in, to make the preauth system even more user friendly and it passed and a lot of the changes in the bill came from CareFirst because we were interested in trying to make the process easier for you. Now it’s up to a year preauth, we’ll auto-populate data for the patient. And there are a couple other less administratively burdensome requirements that we worked on together that hopefully make a difference.

Brian Wheeler: Our formularies are all available online and are organized by therapeutic class. If there’s five or ten things that you’re prescribing on a pretty routine basis, it’s very easy to go figure out what is the, if you’re prescribing something that’s, you know, you don’t prescribe very often. Let’s go and look it up potentially.

Deb Rivkin: Technology clearly, is moving quickly. There’s a software that would show real time benefits and it’s a national platform and the goal is that everyone can use it and it’s going to make everyone’s life easier because it’s in one place, the provider doesn’t have to go into the CareFirst website and then United’s website and Medicare and Medicaid for CVS. It’d be available to everyone, everywhere. It’s a platform that’s important. I think Medicare is going to require it and maybe a couple of years from now (2020). I think it’s moving that direction and maybe that will solve the problem.

Brian Wheeler: Yeah! My favorite topic. We have been working with a tech company for years to develop a clinical data repository. This company has the ability to connect to 160 different electronic medical record types. So, eClinical Works, Athena, you name it, they can connect to it. They have the ability to take structured and unstructured data fields out of that electronic medical record and organize them in a uniform curated way in the cloud securely and with that we will be able to get to a more true interoperability. If you are seeing a patient that recently saw a cardiologist and that cardiologist is connected to the system and you’re connected to the system, you should be able to see the report from that cardiologist. You should be able to see the data across the healthcare system for tests that have been done. A trend in blood pressure, A1C over time. It’s a true unified longitudinal place for any electronic medical record that’s connected to the system and we’re launching it right now. We’ve been developing it for 10 years. It’s going to take another year for maturity and to get all the features out of it that we’d like to get out of it and to be able to make all these things available to providers in the community. So we’re really excited about it. And we’re not aware of anybody else in the country who’s doing anything quite like it. And we’re literally just launching within the last month. So you’ll be hearing more about this in the coming months.

PCMH Model

Question: Many physicians choose to participate in the PCMH model because they believe the medical home model will improve continuity of care for their patients and reduce unnecessary and duplicative tests, and reward their practice’s efforts accordingly through cost savings. Physicians are concerned that the PCMH model is flawed and the Society has had many complaints about high cost patient attribution, lack of incentive payments and/or CareFirst’s inability to rectify the flawed system. High cost patients are often attributed to practices even though the practice has not seen the patient for more than two years, and has repeatedly reached out to the patients with no success. What recourse do these practices have?

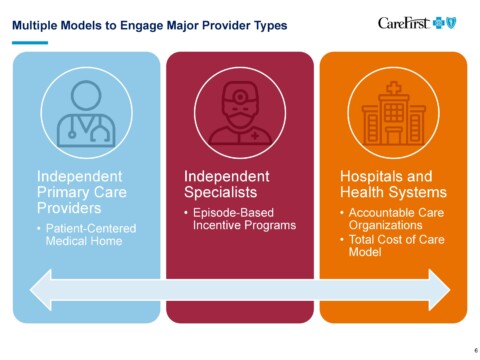

Brian Wheeler: The way that the attribution—every model like, ACOs, Medical Homes—all have an attribution logic. Our attribution logic says that if there has been a visit at your practice by this member in the last two years, they’re attributed to you. That also means that they haven’t seen anybody else. So if the last interaction that they had was 23 months ago, it was at your practice. They’re attributed to you. If the patient hasn’t seen you in more than 24 months and they’re attributed to you, it’s because when they did their annual open enrollment and they were an HMO member, they selected you as their primary care physician. Those are the only two ways that they could be attributed. Either they’ve seen you or they said, I haven’t been to the primary care physician, but if I did, I’d go to this doctor and they selected you in our system. That’s how you get attributed.

Audience Member: If a patient is in a PPO and they’re going wherever they want, and you’re calling and saying “no, we really need to get you back in here” and they won’t come: why are we being held responsible?

Brian Wheeler: Yes, we [CareFirst] are ultimately responsible because we’re still paying the cost. We would like the primary care community to do the outreach necessary to get the patient in and to manage them. They’re not going to listen to us. They’re going to listen to you because you’ve got the holy pulpit of the physician. It’s an accountable care program. You become accountable for the patient in this way and then we expect you to manage the patient and we pay you extra to do so. That’s how it works. That’s how the program works.

Audience Member: But if I’ve done all the outreach, and I’ve documented that they refuse to come-

Brian Wheeler: I would suggest that you look out across the industry and you see how these models are structured. Every single one of them has an attribution model where people become attributed to a particular position or accountable care organization because of the certain logic and ours is extremely precise. It’s the ninth year of the program. We’re pretty good at this at this point. This is the way the patients get attributed to panels. I would also say it’s probably a very small number of patients that this is occurring with, very small, because only 3% of our population is really sick. It’s a commercial population. It’s a very small number of people. If you’ve got a thousand members, you’ve got a very small number who really need this kind of additional attention and so to take the data that we give you in the system and reports and make sure that you’re really focused on the population that’s doubling up with those additional costs and claims is the true success for the program. Is it possible that you will have a patient or two that becomes high cost, but it’s a population based program. It’s not about one or two patients. It’s about managing the population.

Audience Member: The problem is this dis-incentivizes physicians from seeing patients with a number of co-morbidities when, for the next two years, my practice will be responsible when they aren’t compliant.

Brian Wheeler: So you interview patients and turn them away?

Audience Member: No, but it might cause that.

Brian Wheeler: It’s never caused that before. I would also say that if you had a patient that goes above $85,000 in a year, you’re protected for costs that go above that. Whether the patient’s seen you or not, you’re still getting a budget for that patient in your budget on a monthly basis. We have built some protections in to understand that there are extraordinary cases. I have spent a lot of time looking at these models across the country. This is the absolute best model of its kind that’s available in the United States. None of them are going to be perfect. There’s no such thing as perfection. This is the best. This is the state of the art in the United States for primary care medical homes.

Lawrence Green, M.D.: Obviously this is a concern for us and, we have ideas on how to fix this. This can be part of our ongoing dialogue.

Brian Wheeler: We would welcome any suggestions that you have, but there are certain brackets that we have to operate within.

Lawrence Green, M.D.: But this is a chance for us to collaborate.

Question: In the PCMH model, primary care physicians are held financially responsible for decisions made by specialists. One practice ended up $2M in the red because of this. How can PCPs avoid being penalized in the future?

Brian Wheeler: Two things. One, the $85,000 stop loss, you’re protected after that. Those are probably going to be pretty sick patients at that point. They’ll be generating a lot of budget into your credits in your credit account for the program. But after $85,000, you’re only going to be responsible for 20% of the costs. So it dramatically reduces the amount that that goes into the practice budget for that particular year. I would also say that we talked to a number of primary care physicians and there’s, you know, in any profession there’s variation. Primary care physicians who sit down with their patients and really contract with them, come up with a deal. If you’re going to be my patient, I’m going to be your physician, you’re going to come to me, you’re going to run things through me. I have a network of specialists that I work with and cooperate with. You will get in faster to see them if you go to those particular specialists, if you use my name, I will get reports back from them more quickly. We will coordinate on your prescribing.

Physicians who have conversations with patients like that are less likely to have patients that go all over the place. That’s not to say that some won’t, but they’re more likely to come to you if you built that trust relationship. There are sort of three cohorts. There are patients who are going to go wherever they want, no matter what you do. That is true. There are patients who are never going to go anywhere without talking to you. And then there’s the movable middle. The movable middle is where you can make a difference in a population health program like this.

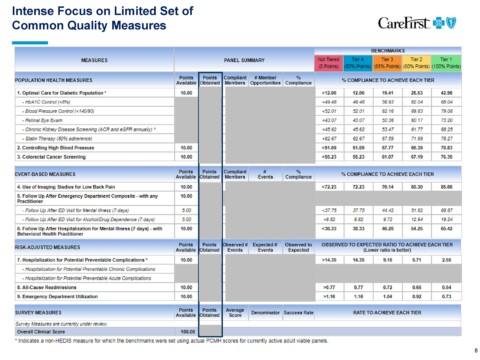

Audience Member: PCMH structure pays lip service to quality and patient experience, but the focus always seems to be on cost. So what is your response?

Brian Wheeler: Two things: I’d say that it’s lip service to cost. Quality is a gate to getting an outcome incentive award and the quality requirements have increased every year since the program began. And we’ve seen improvements in quality according to the way that it’s measured by NCQA since the program began and cost is an important factor. We can’t share savings unless there are savings to share. And savings means meeting a particular trend for the population over time. We believe is a big issue in access to care. If rising cost threatens access, then there’s no better way to improve access then to follow the rising costs. So I wouldn’t say that it’s an inappropriate thing to keep costs as a focus, but you can’t get paid for shorting on quality in the program. That’s why we have gates.

Physician Rating System

Question: According to the current state law, CareFirst’s tiering system does not qualify as a physician rating system; however, CareFirst’s “tiering” practices are having a similar, if not greater impact, on referral patterns and continuity of care. 1) Please explain the quality and cost criteria used in CareFirst’s system of categorizing physicians in color-coded tiers (red, yellow, green). 2) What education has CareFirst done to help participating physicians understand the tier system? 3) Are physicians penalized who refer to physicians who are “red” physicians? 4) How can physicians appeal their tier placement?

Brian Wheeler: This is actually about an hour long presentation. We can do another time but I’ll tell you briefly how the program works. We take all events, 35-45 million a year, and then we have these analyticals called groupers. And what a grouper does is, let’s take a knee replacement, it’ll find a knee replacement and it will say, oh, there’s a knee replacement. I’m going to look back 90 days and forward 60 days and see all the claims that were in that cohort around that knee replacement. Same with pre-ops and physical therapy after the surgery and the anesthesiology. And then I can look and the groupers have this technology that says, oh wait, that’s a structural. We’re going to pull that out. That’s not related to the knee or you know, that’s something else that’s not labeled. Pull that out as well. What you end up with is a knee replacement and all the things related to the knee replacement, which becomes the unit of measure. That unit of measure cleaned that way with all the inclusions and exclusions can be compared against all the other knees that were done in all the other hospitals across the CareFirst network in a given period.

So now we’re comparing knees with knees with knees and before you know it, we’ve got 6,000 knees to compare. Those knees each had a cost outcome that came along with them. Some of those knees were $30,000, some of them were $15,000, some were $11,000 and all of these with all of those costs were done by a particular specialist, maybe three or four of these were done by a particular specialist. What happens is the pattern emerges that some specialists consistently do $30,000 knees and some specialists consistently do a $12,000 and you can begin to predict when that specialist does the knee, what the cost is going to be. So if a primary care physician needs to refer someone and they believe they’re going to have a knee replacement, it’s really helpful to them to understand that this physician is going to do the knee replacement in the OR at an academic medical center. And this physician is going to do the knee replacement at an endosurgery center that may be doing frequent knee replacements. So it’s a way of helping the primary care physicians understand what we can take into account.

Audience Member: But some physicians will get the more complicated cases, some people are getting a lot of routine cases and so that person’s costs are going to be higher, but that’s because they’re handing different types of episodes.

Brian Wheeler: Groupers group together like episodes. We can go more into detail, but if you’re doing more complex colonoscopies, you’re compared against others who did more complex colonoscopies, not against routine colonoscopy.

Audience Member: So, where do you check to see if the patients at different cost levels kept their weight down after that knee surgery? Where do you do data sets? The product that would be a longer term cost might be the less expensive one. So how do you measure that?

Brian Wheeler: This is a measure of cost only. We do not make any quality judgment and when we share this information with primary care physicians, we say that we’re not making any quality adjustments. We trust that the primary care physician knows the providers in the community and knows the outcomes that they’re getting. The only question, the only thing they don’t know and never had information about is the cost and utilization pattern of that particular specialist that’s lower. We’re providing that to the primary care community.

Audience Member: Why do specialists have to find out from primary care physicians in our community that we have a poor rating? Why isn’t it sent to us directly? Why won’t CareFirst provide a clear response about what’s driving the rating down?

Brian Wheeler: Use our contact information. We’d be happy to provide you the information. We do a monthly webinar that all specialists, all primary care are invited to. The next one is on September 26th at 5:00 PM. What we do is go through a detailed methodology. I just gave you the 30 second version of how costs are grouped and ranked, but we give you a full review of the detail of how it works and then any specialist who comes to the presentation, we’re happy to send your individual 10 page report cards with all the details of how you vary from your peers on those.

Deb Rivkin: This is a great dialogue because it means that specialists are now saying, oh my God, what do I do? Because maybe we can have a change. Either you can reach out, we have to reach out, we can do a better job to reach out to you. But this might be that opportunity to say, what can we do to make sure that we’re doing something so the referrals will continue to come with us because we don’t want to be red. What can we do to make a difference? This is a positive thing in my mind. We’ll work toward automatically sending these reports to every specialist.

Brian Wheeler: I’m very passionate about this stuff. This is a great beginning of the dialogue, but as Dr. Green said, let’s not let this be the end of the dialogue. Let’s get you connected with the right people so that you get the data that you need, understand why things are the way they look in the data and how the methodology works, and then have a follow-up conversation about it thereafter.

Fee Schedule Updates

Question: A physician of an in-demand critical care specialty reports “My practice has not had a fee schedule update since 2008. CareFirst has refused to raise our rates unless I provide comparisons to all other payers.” The Society regularly hears from physicians who are compensated 25-30% more for the same code in Northern Virginia. This has an impact on patient access to care in Maryland. 1) What is your policy and process for review of fees and the frequency for which this is done? 2) In Maryland CareFirst’s fee schedule is often well below Medicare rates. Why are the CareFirst fee schedules significantly more in other states?

Brian Wheeler: The fee schedules aren’t as much my thing. I evaluate programs, but I know a lot about it and I’ll take a shot at answering. First of all, there is a fee schedule for the DC metropolitan area, including northern Virginia. Fee schedules in northern Virginia are the same as what gets paid here in Montgomery County. There are different organizations that have negotiated different rates. That is true. Perhaps that’s where that information is coming from. There is a process through your provider relations representative. Everyone should have a CareFirst professional provider relations representative to increase the request or review your fee schedule. And then there’s a process where the practice is viewed versus other practices in the area market rates to assure that there’s sort of a rational market distribution of fees. So that’s the process.

Lawrence Green, M.D.: The experience of the group, including myself, is that when we asked for a fee schedule increase after many years we are consistently denied.

Brian Wheeler: I can be an ambassador and help you get in touch with the right people and we’re happy to do that.

Audience Member: When will the policy change to send the payment directly to the surgeon who performed the surgery for payment of that service?

Brian Wheeler: The physicians have control over that. They can join the network and then they can get paid directly by CareFirst. If they don’t join the network, the payment will never go directly to the physician and it will always go to the patient. The patient is who we have a contract with at that time. And if the patient goes to a physician we have a contract with, we pay the physician who we have a contract with on behalf of the patient. If a patient goes to a physician that doesn’t have a contract with us, we have no basis to pay that physician. We have no choice but to pay the patient. And the percent of claims that we have that go to out-of-network providers is insignificant, less than 2%.

Lawrence Green, M.D.: Members have expressed the difficulty of being able to reach provider relations and contracting, that there’s no continuity, that it’s difficult to get information, difficult to get phone numbers and addresses. How can we always make sure that we have the right contact people?

Brian Wheeler: We’ll send you a list by county, by specialty, by provider type of who to contact and that your members can contact. Obviously it should be on our website and accurate as well, but if they’re more comfortable contacting you, we’ll get you the current name, email address and phone number for each of those different contacts.

Prior Authorization Requirements

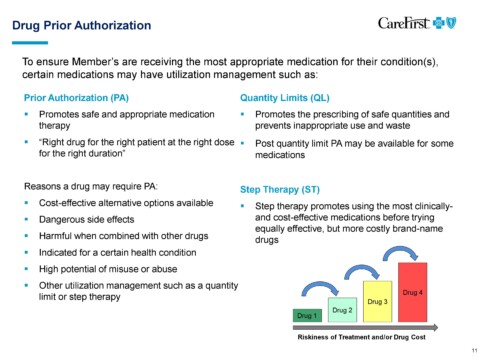

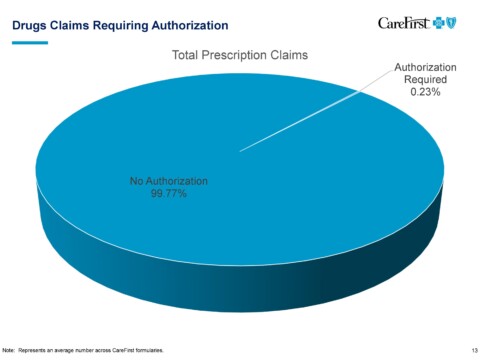

Question: According to MCMS’s 2019 Practice Survey, 45% of physician respondents and their staff spend between 2 – 5 hours per on nonclinical record keeping. 28% of physician respondents spend 2-7 hours per day obtaining prior authorizations. 6% of physician respondents indicate they spend more than 8 hours per day obtaining prior authorizations. According to the AMA’s recent survey of 1,000 physicians, more than nine in 10 respondents said PA had a significant or somewhat negative clinical impact, with 28 percent reporting that prior authorization had led to a serious adverse event such as a death, hospitalization, disability or permanent bodily damage, or other life-threatening event for a patient in their care. The vast majority of physicians (86 percent) described the administrative burden associated with prior authorization as “high or extremely high,” and 88 percent said the burden has gone up in the last five years. 1) Prior authorization has added layers of administrative red tape to the medical care delivery process, and increased physician burnout and has been shown to have negative patient care implications. Will CareFirst continue to require prior authorizations? 2) CareFirst’s prior authorization rules require physicians often to go through step therapy protocols even though they know what medication or therapy is best for a particular patient’s condition. This often causes delays in getting patients the treatment they will best respond to. How can CareFirst ease this process and trust that physicians will make the right decisions for their patients?

Deb Rivkin: Let me try to level set a little bit. When I was talking before about the laws that we put in place for Maryland to try to ease the problems for step therapy as well as for preexisting conditions, that only applies to plans that are fully insured. I don’t want to get into anything too esoteric, but Medicare picks their own rules. State of Maryland picks their own rules. If you’re an employee at a self-funded employer, you’re being insured by the company. You’re actually asking them to administer the plan for you. You can decide what you want. So we try to put-part of the problem in my humble opinion for this whole mess that we have with insurance is because there’s lots of rules because the laws that we’ve worked on together or sometimes not necessarily together only apply to a small percentage of your patients. The fully insured population in Maryland is under, I think it’s 30% of the under 65 marketplace. So Medicaid has their own. So you pick them out. Medicare, their own. Like I said, every county school board, they’re all self-funded and so they don’t have to follow the things that we put in place. So that’s, I think, part of this frustration too.

Formulary Decisions

Question: Health plan formulary decisions have significant patient care ramifications. The administrative burden of justification of appropriate medications also adds to the red tape physicians must go through on behalf of their patient to get the appropriate medication. 1) Please explain the process by which CareFirst selects which drugs are formulary vs. other tiers for its various plans?

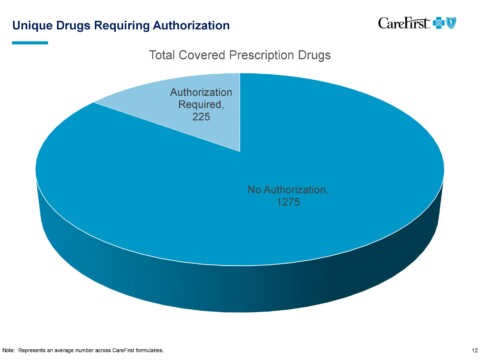

Brian Wheeler: CareFirst has contracted with the CVS Caremark to provide the formulary management. We used to manage it in-house, but three or four years ago we decided to work with CVS Caremark. We delegated that responsibility to them. The way that the CVS Caremark formulary process works is that there is a group of practicing physicians, pharmacists as well as a medical ethicist, all of whom are on a panel that’s called The Pharmacy and Therapeutics Committee. The names of these people are kept secret because they need to be kept free of influence. They go through extensive conflicts checks to make sure they’re not receiving research money from anyone or employed by anyone or getting trips, gifts from anyone or anything else. So it’s a very rigorous process of making sure these people are completely clean in their judgment. They are shown scientific information about the effectiveness and side effects of drugs and various therapeutic classes. And they approve or reject particular drugs to be available in the formulary and therapeutic classes. They do this without any information about cost then, the list of potential eligibles for a particular therapeutic class, it goes to business people who then try to get the best cost for the options in that particular therapeutic class. The process of making clinical determinations about what’s in the therapeutic class is made by folks who are completely clean of influence.

Lawrence Green, M.D.: Our view is different. We see medications that are approved, especially expensive medicine, even step therapy are the ones that give Caremark the largest kickback. It seems to be, the bigger the kickback you’d get, the more approved medicines you give.

Brian Wheeler: Rebates certainly factor into the way these things are designed. CareFirst doesn’t influence that directly. We have ceded it to Caremark. We’d prefer that you’re not getting rebates at all. We would prefer the generic be prescribed in every single case. But unfortunately there are cases where particular brands or large molecules are necessary to care for a patient. In that case, they need to be prescribed. We wouldn’t want to stop patients from getting something that they need, but in every case you could prescribe a generic drug, please prescribe the generic drug because the increases in cost of the drug is crowding out our ability to fund other things in other places. That’s the reality.

Deb Rivkin: They’re not kickbacks, so I bristled when you said that. They’re rebates but there’s a difference and honestly that is to help us get the price down for all patients because what they do is they’ve agreed to a lower price that we will put them on the formulary and the money we get goes everyone. It lowers our premiums for everyone. We’re a nonprofit health service plan. We don’t have stockholders. We’re not out to make a profit. In the nine years that I’ve been with CareFirst, over seven of them we made less than 1%. We are not high rollers, so that money is not coming back to CareFirst. If we’re able to get a rebate, that money is going back in everyone’s rates to make them lower.

Network Adequacy

Audience Member: How does CareFirst evaluate its physician panel to ensure network adequacy?

Brian Wheeler: We know where all our providers work and we have the ability to take them by address, by practice location and map them. So we do geo access to meet the standards of patient access within a certain number of miles. There are different standards for rural versus urban areas. We’re constantly monitoring the capacity of practices as well. If we find that we have a shortage we reach out to providers to increase access.

Deb Rivkin: In our network, we don’t close our panels. Anyone who comes and meets our credentialing standards is welcome to join CareFirst in our regional PPO. We’re not like other carriers and say we’ve got too many of something. Secondly, when we find that we’ve got areas that we do have difficulty, we do reach out. So for example, a psychiatrist, psychologist? Really difficult for us to get them into network. A lot of them in Montgomery County do not choose to come into network. We send letters, we increased fee schedules. We went out and talked to them. We actually looked in our claims data and said, you are someone who is seeing a lot of CareFirst patients out of network. And so we reached out to those that are seeing our patients, asking them to come in. We try to become creative and will look at other providers. So LCSWs, no one else was allowing them to be in their network. We were the first, because we needed to try to expand access. So we really are doing our best to try to make sure that we have all specialties, you know, as much as we can and that we can meet the needs of our members. We work hard on that.

Brian Wheeler: Another thing that really can help is practice economics and we’re doing a lot of work, you know, back to the questions about our fee schedules and stuff. We’re starting to do a lot of work of understanding the economics of running a practice, we’re actually buying data sources to understand what practice expenses are. We can model revenue based on what we know we’re paying, to see how the practice is doing because we want to have healthy, sustainable practices in the community. We’re doing more and more of this work and we’re finding that in a lot of practices, not all specialties, but the use of mid-levels can really help with the practice and profitability and free the position up and help reduce physician burnout. So we’re modeling these things and hopefully within about six months we’ll have some presentations, where we’re going to have our own position on what the ideal practice structure looks like, what the revenue should be, working expenses should be, what kinds of providers should be employed to generate revenue, what the margin is on those particular providers so that we can really work together to have healthier practices across the state. We’re buying the MGMA data and we’d be happy to collaborate with you as well. We can benchmark against each other.

Audience Member: What causes inaccurate listings on your provider lists?

Deb Rivkin: We still have a contract with them and they never terminated. We actually have a link on our website and I’ve used it for myself. When a patient knows that a doctor is no longer in network or castaway, or no longer practicing, they can report it to us because we’re only as good as information we get. Period. So we’ll do a number of things. I knew my physician had retired, so I reported it, then logged back in and saw he’d been removed. So the patients are a great way to do that. Number two, we look at claims. If we haven’t seen a claim for you in six months, we try to check. We look at obits, we do a lot of things. We’re always sweeping. We are really working to try to be the best. And we’re hoping that physicians will help us there as well.

Brian Wheeler: I know that we’re not always going to be 100% aligned, given each of our roles in this healthcare economy. But we have a big problem that we have to collectively solve together and we were glad to be here tonight. The reason we’ll continue to engage is we want to search for ways to find alignment. You have to understand the pressures that are on us. We have to better understand the pressures that are on you and figure out how to solve the problem collectively. So I appreciate MCMS inviting us tonight and I do want to continue this dialogue in a number of different avenues and I have a whole team of people who I’m happy to have come out to your offices and go through information in more detail with you as well.